- Home

- Robert McCammon

1987 - Swan Song v4

1987 - Swan Song v4 Read online

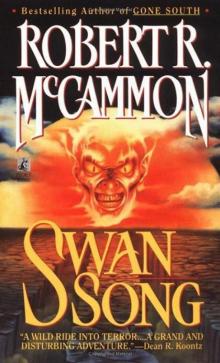

Swan Song

* * *

EDITORIAL REVIEW:

“We’re about to cross the point of no return. God help us; we’re flying in the dark and we don’t know where the hell we’re going.”

Facing down an unprecedented malevolent enemy, the government responds with a nuclear attack. America as it was is gone forever, and now every citizen—from the President of the United States to the homeless on the streets of New York City—will fight for survival.

Swan Song is Robert McCammon’s prescient and “shocking” (John Saul) vision of a post-Apocalyptic nation, a grand epic of terror and, ultimately, renewal.

In a wasteland born of rage and fear, populated by monstrous creatures and marauding armies, earth’s last survivors have been drawn into the final battle between good and evil, that will decide the fate of humanity: Sister, who discovers a strange and transformative glass artifact in the destroyed Manhattan streets . . . Joshua Hutchins, the pro wrestler who takes refuge from the nuclear fallout at a Nebraska gas station . . . And Swan, a young girl possessing special powers, who travels alongside Josh to a Missouri town where healing and recovery can begin with Swan’s gifts. But the ancient force behind earth’s devastation is scouring the walking wounded for recruits for its relentless army, beginning with Swan herself. . . .

I've always thought that any kind of film based on a book or short story can be a fascinating experience for the author---not necessarily because the film is good or bad, but because it's a reflection of how other people visualize the author's words. A writer creates the word pictures, and then people who weren't directly involved in that creation process have the task of making the word pictures solid. But I think the real challenge of being a writer is to create a mental movie: doing the lighting, the costumes, the casting and makeup, the special effects, the directing and making sure all the props are there on cue. I hope the readers do approach my books as films, that they can see in their minds as they read. The devil, it's been said, is in the details. If the details aren't there, a scene often lacks vitality.

Which is a long way of getting around to writing that the illustrated version of Swan Song has just been published by Dark Harvest, and it was an interesting experience for me to see how an artist visualized scenes from the mental movie I'd created. The details are right. If something was in the scene, it's there in the illustration. So I want to thank Paul Mikol and the two artists who worked on the book, Charles and Wendy Lang, for an excellent job. Paul Mikol promised me Dark Harvest's production of Swan Song would be a quality work, and the Langs added an extra dimension of quality that I feel very, very proud about.

All books are like children. They develop their own personalities as they're written. Some of them are sweet and gentle, others are nasty bullies, some don't want to grow up, others jump ahead so fast they pull you along by the throat. This, strangely enough, has nothing to do with length or complexity. It just is. No book I've ever written has been born in quite the same way, though my work patterns don't vary. Swan Song was a relatively easy birth, in that it flowed smoothly from beginning to end. Stinger was a beast; about sixty pages from the end, I realized I'd made a major goof and had to go back two hundred pages and start from there again. Usher's Passing almost put me under, but Mystery Walk was easy. The Wolf's Hour was really fun to do, probably the easiest birth of all even though it went back and forth between time periods. But my latest book---called MINE---was much tougher, even though the story is simple and straight-ahead. So it's hard to tell what the child will be like until you get into the birthing process. You just have to grit your teeth, hope for the best, and prepare to face the detail devil again.

I was asked to talk about how and why I wrote Swan Song. I'd like to tell you why I don't want to do that.

Swan Song, even though the new hardback version is out and it looks terrific and I hope it does very well, is ancient history to me. I got a letter not long ago addressed to Robert "Mr. Swan Song" McCammon. Now: let me say first of all that I'm really, really glad readers responded to Swan Song, and that the book continues to speak to people about hope in a world where hope seems to be a dirty word. That's great---but I'm not satisfied. I want more. Not more money, not more fame, not movies and "celebrity status." I want more from myself, and I don't plan on letting anybody believe for a second that Swan Song is going to be a laurel wreath on my head.

I'm going to write better books. I'm going to write ones not as good. But the point is, I'm going to write different books. Many people have written urging me to do a sequel to Swan Song. I leave most of my books open for sequels---not so I can write them, but so readers can carry the story line further along in their imaginations. Sequels are never as good as originals, and almost always disappointing. Having said that, I also have to say that I am kicking around the idea of doing a sequel to The Wolf's Hour in three or four years. I would do it because I really enjoyed writing the original, because I would have something different to say, and because I might be interested in doing a series of books that span the continuation of Michael Gallatin's line into modern times. It would not be The Wolf's Hour Part II. Believe it.

For me, writing is a great freedom. I don't use an outline. I don't usually know what's going to happen from one point to another, though I develop what I call "signpost scenes" as a kind of free-form roadmap. Writing is a great adventure, a journey of faith into the unknown. Sometimes it's a night trip, and you lose your way for a while. But when you get to your destination, and see the home fires burning, the joy is beyond description.

I almost gave it up, a while back. I got really tired of hearing things like "the poor man's Stephen King," and that I was "walking on King and Straub's territory," that I was a rip-off artist and a hack with no style of my own. I almost said to hell with it, and for a while I was looking through the want ads trying to figure what else I could do.

When I reached the bottom of that particular pond, I realized there was nothing else I could do besides write. For better or worse, I was married to writing, and I had to keep going no matter what was shoveled at me.

So here we are.

I'm not always going to write horror novels.

The new book, MINE, isn't a horror novel in the supernatural sense, though it certainly is horror in the real world. I may do a fantasy novel next. I have a science-fiction book in the early stages. I'm planning on doing a love story---of a sort---set in the 1600s. I may do a book of the further adventures of Poe's detective, Dupin. Whatever: the point is, writing is the freedom to go and do and be and see, and I have no idea of where the boundaries lie.

As I said before, I might write books that are better than others, but of one thing I'm certain: I won't repeat myself. Neither will I stop trying to become a better writer. Easy to say, hard to do. I know where the want ads are; I've seen their gray solemnity and invitation into a world of locks and keys. I can't live there.

Again, I want to thank Paul Mikol and the Langs for an excellent job on Dark Harvest's production of Swan Song. And for knowing that the devil is in the details.

What's past is preface. We go from here.

“KING, STRAUB, AND NOW ROBERT McCAMMON…”

– Los Angeles Times

AN EPIC JOURNEY OF TERROR ACROSS A LAND SEETHING WITH UNSPEAKABLE HORRORS. AMERICA! – HAUNTED BY AN EVIL WHOSE TIME HAS FINALLY COME.

An ancient evil roams the blasted, nightmare country, an evil as old as time. He is the Man with the Scarlet Eye, the Man of Many Faces, gathering under his power the forces of human greed and madness. He is seeking to destroy a child, the one called Swan.

From Robert R. McCammon, one of the living masters of horror, comes a stunning tale of sheer fright and power where the end of the

world is just the beginning of mankind’s ultimate struggle.

“A CHILLING VISION THAT WILL KEEP YOU TURNING THE PAGES TO THE SHOCKING END.” – John Saul

On the edge of a barren Kansas landscape, a man called Black Frankenstein hears the cry… “PROTECT THE CHILD…”

In the wasteland of New York City, a bag lady clutches a strange bejeweled ring and feels magic coursing through her…

Within an Idaho mountain, a survivalist compound lies in ruins, and a young boy learns how to kill…

In a wasteland born of nuclear rage, in a world of mutant animals and marauding armies, the last people on earth are now the first. Three bands of survivors journey toward destiny—drawn into the final struggle between annihilation and life!

THEY HAVE SURVIVED

THE UNSURVIVABLE.

NOW THE ULTIMATE TERROR BEGINS.

For Sally, whose inside face is as beautiful as the one outside. We survived the comet!

————————————

This novel is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

The author is grateful for permission to quote from “The Waste Land” from Collected Poems 1909-1962 by T. S. Eliot, copyright 1936 by Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc.; © 1963, 1964 by T. S. Eliot. Reprinted by permission of the publisher.

Another Original publication of POCKET BOOKS

POCKET BOOKS, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, N.Y. 10020

Copyright © 1987 by The McCammon Corporation

Cover artwork copyright © 1987 Rowena Morrill

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Pocket Books, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, N.Y. 10020

ISBN: 0-671-62413-X

First Pocket Books printing June 1987

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

POCKET and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Printed in the U.S.A.

BOOK ONE

One

The Point of No Return

Once upon a time /

Sister Creep / Black

Frankenstein /

The spooky kid /

King’s Knight

One

Once upon a time

July 16

10:27 P.M. Eastern Daylight Time

Washington, D.C.

Once upon a time we had a love affair with fire, the president of the United States thought as the match that he’d just struck to light his pipe flared beneath his fingers.

He stared into it, mesmerized by its color—and as the fire grew he had the vision of a tower of flame a thousand feet tall, whirling across the country he loved, torching cities and towns, turning rivers to steam, ripping across the ruins of heartland farms and casting the ashes of seventy million human beings into a black sky. He watched with dreadful fascination as the flame crawled up the match, and he realized that there, on a tiny scale, was the power of both creation and destruction; it could cook food, illuminate the darkness, melt iron and sear human flesh. Something that resembled a small, unblinking scarlet eye opened in the center of the flame, and he wanted to scream. He had awakened at two in the morning from a nightmare of holocaust; he’d begun crying and couldn’t stop, and the first lady had tried to calm him, but he just kept shaking and sobbing like a child. He’d sat in the Oval Office until dawn, going over the maps and top-security reports again and again, but they all said the same thing: First Strike.

The fire burned his fingers. He shook the match out and dropped it into the ashtray embossed with the presidential seal in front of him. The thin thread of smoke began to curl up toward the vent of the air-filtration system.

“Sir?” someone said. He looked up, saw a group of strangers sitting in the Situations Room with him, saw the high-resolution computer map of the world on the screen before him, the array of telephones and video screens set in a semicircle around him like the cockpit of a jet fighter, and he wished to God that someone else could sit in his seat, that he was still just a senator and he didn’t know the truth about the world. “Sir?”

He ran his hand across his forehead. His skin felt clammy. Fine time to be coming down with the flu, he thought, and he almost laughed at the absurdity of it. The president gets no sick days, he thought, because a president’s not supposed to be sick. He tried to focus on who at the oval table was speaking to him; they were all watching him—the vice-president, nervous and sly; Admiral Narramore, ramrod-straight in his uniform with a chestful of service decorations; General Sinclair, crusty and alert, his eyes like two bits of blue glass in his hard-seamed face; Secretary of Defense Hannan, who looked as kindly as anyone’s old grandfather but who was known as “Iron Hans” by both the press corps and his associates; General Chivington, the ranking authority on Soviet military strength; Chief of Staff Bergholz, crewcut and crisp in his ubiquitous dark blue pin-striped suit; and various other military officials and advisors.

“Yes?” the president asked Bergholz.

Hannan reached for a glass of water, sipped from it and said, “Sir? I was asking if you wanted me to go on.” He tapped the page of the open report from which he’d been reading.

“Oh.” My pipe’s gone out, he thought. Didn’t I just light it? He looked at the burned match in the ashtray, couldn’t remember how it had gotten there. For an instant he saw John Wayne’s face in his mind, a scene from some old black-and-white movie he’d seen as a kid; the Duke was saying something about the point of no return. “Yes,” the president said. “Go on.”

Hannan glanced quickly around the table at the others. They all had copies of the report before them, as well as stacks of other Eyes Only coded reports fresh off the NORAD and SAC communications wires. “Less than three hours ago,” Hannan continued, “our last operating SKY EYE recon satellite was dazzled as it moved into position over Chatyrka, U.S.S.R. We lost all our optical sensors and cameras, and again—as in the case of the other six SKY EYEs—we feel this one was destroyed by a land-based laser, probably operating from a point near Magadan. Twenty minutes after SKY EYE 7 was blinded, we used our Malmstrom AFB laser to dazzle a Soviet recon satellite as it came over Canada. By our calculations, that still leaves them two recon eyes available, one currently over the northern Pacific and a second over the Iran-Iraq border. NASA’s trying to repair SKY EYEs 2 and 3, but the others are space junk. What all this means, sir, is that as of approximately three hours ago, Eastern Daylight Time”—Hannan looked up at the digital clock on the Situation Room’s gray concrete wall—“we went blind. The last recon photos were taken at 1830 hours over Jelgava.” He switched on a microphone attached to the console before him and said, “SKY EYE recon 7-16, please.”

There was a pause of three seconds as the information computer found the required data. On the large wall screen, the map of the world went dark and was replaced by a high-altitude satellite photograph showing the sweep of a dense Soviet forest. At the center of the picture was a cluster of pinheads linked together by the tiny lines of roadways. “Enlarge twelve,” Hannan said, the picture reflected in his horn-rimmed eyeglasses.

The photograph was enlarged twelve times, until finally the hundreds of intercontinental ballistic missile silos were as clear as if the Situations Room wall screen was a plate glass window. On the roads were trucks, their tires throwing up dust, and even soldiers were visible near the missile installation’s concrete bunkers and radar dishes. “As you can see,” Hannan went on in the calm, slightly detached voice of his previous profession—teaching military history and economics at Yale—“they’re getting ready for something. Probably bringing in more radar gear and arming those warheads, is my guess. We count two hundred and sixty-three silos in that installation alone, probably housing over six

hundred warheads. Two minutes later, the SKY EYE was blinded. But this picture only reinforces what we already know: the Soviets have gone to a high level of readiness, and they don’t want us seeing the new equipment they’re bringing in. Which brings us to General Chivington’s report. General?”

Chivington broke the seal on a green folder in front of him, and the others did the same. Inside were pages of documents, graphs and charts. “Gentlemen,” he said in a gravelly voice, “the Soviet war machine has mobilized to within fifteen percent of capacity in the last nine months. I don’t have to tell you about Afghanistan, South America or the Persian Gulf, but I’d like to direct your attention to the document marked Double 6 Double 3. That’s a graph showing the amount of supplies being funneled into the Russian Civil Defense System, and you can see for yourselves how it’s jumped in the last two months. Our Soviet sources tell us that more than forty percent of their urban population has now either moved outside the cities or taken up residence inside the fallout shelters…”

While Chivington talked on about Soviet Civil Defense the president’s mind went back eight months to the final terrible days of Afghanistan, with its nerve gas warfare and tactical nuclear strikes. And one week after the fall of Afghanistan, a twelve-and-a-half-kiloton nuclear device had exploded in a Beirut apartment building, turning that tortured city into a moonscape of radioactive rubble. Almost half the population was killed outright. A variety of terrorist groups had gleefully claimed responsibility, promising more lightning bolts from Allah.

Swan Song

Swan Song The Wolfs Hour

The Wolfs Hour Ushers Passing

Ushers Passing Mine

Mine The Queen of Bedlam

The Queen of Bedlam Baal

Baal Boys Life

Boys Life Speaks the Nightbird

Speaks the Nightbird The Hunter from the Woods

The Hunter from the Woods Mister Slaughter

Mister Slaughter The Night Boat

The Night Boat Bethanys Sin

Bethanys Sin Mystery Walk

Mystery Walk Gone South

Gone South Cardinal Black

Cardinal Black I Travel by Night

I Travel by Night Last Train from Perdition

Last Train from Perdition 1987 - Swan Song v4

1987 - Swan Song v4 The River of Souls

The River of Souls The Border

The Border 1990 - Mine v4

1990 - Mine v4 1988 - Stinger

1988 - Stinger The Listener

The Listener