- Home

- Robert McCammon

The Listener Page 4

The Listener Read online

Page 4

By the end of this, John Partlow himself could hardly cross his legs and if he didn’t know better he would have thought Spanish Fly was the greatest invention for men since Eve. It came as no surprise to him when Ginger opened the cardboard box and with a sexy flair and knowing smile showed the yokels the bottles of Tijuana Joy Juice for sale at one dollar a throw.

John Partlow sat and watched the men swarm to the stage with their money in hand.

They were going not only to get lit up by the juice—a questionable result, since the brown liquid in the bottles was likely only stale cola flamed with a little dash of cocaine—but to get the woman to look them in the eyes with that slow fever-burn she was exhibiting, or to breathe a whiff of her scent or get a touch of Ginger-flesh. Anyway, not all the rubes could afford a buck for a bottle but most coughed it up, and John Partlow figured Ginger and the doc were going to clear another thirty skins, which was not a bad haul.

Then came the most difficult part for the team: getting the marks out of the auditorium so they could pack up and scat. Ginger had done her job so well a knot of overall-clad farmboys with bottles of Tijuana Joy Juice in their paws thought they were one tobacco spit away from an easy score with a red-dressed wanton. They were grinning like little boys and slurping on the lollipops of their dirty imaginations. Several of them kept calling to Ginger as she was taping up the cardboard box for transit and the doc was trying to focus on counting the cash. Therefore John Partlow saw his opportunity, and he quickly walked up to the stage and said loudly, “Ginger, darlin’? You need some help with that? Seems like a husband ought to lend a hand instead of just sittin’ out here watchin’ his wife work.”

She didn’t miss a beat.

“Yeah, babe,” she answered, with just a fast appraisal done by a sidelong glance. “You want to carry this to the car, that would be trim.”

John Partlow nodded. Trim, he thought. Slang in the con game for sliding one past the suckers. “You got it,” he said, and he reached up and took the box as she handed it down.

Around him the knot of men burst asunder and they went on their way, for it was apparent that even their own countrified good looks and so many bottles of joy juice could not compete with a white-suited city dude who looked like somebody’s angel…and, obviously, was.

“Car’s around back,” she told him when she and the doc came down from the stage.

Honeycutt was holding onto her arm for balance, and he looked at John Partlow through bloodshot eyes and rasped, “Who are you?”

“That’s my new husband Pearly,” Ginger said. “Didn’t you know I got hitched up in Knoxville?”

“What?” The doc staggered a step.

“I’m funnin’ you. He’s a charmer, that’s all. Come on now, watch where you walk.”

They went past the Negro man who’d come in to sweep up. Full dark had fallen and the only lights were the shine of a few streetlamps and the glow against the night from the mill to the southwest. John Partlow followed Ginger and Honeycutt around back of the Elks Lodge, carrying the box of unsold joy juice bottles. In a small dirt parking lot was a metallic blue Packard sedan that had a few dents and knocks on it but otherwise looked to be a pretty fine automobile, quite a few steps up from the old tired Oakland.

“You walk from the Nevins’ place?” Ginger asked.

“I did.”

“Keys,” she said to the doc.

“I’m drivin’,” Honeycutt answered, with a defiant lift of his sagging chin. “Feel fine enough to—”

“Keys,” she said again, more firmly. She held her hand out in front of his face. “The car and the room keys both.” She paused a beat. “Remember what happened in Little Rock.”

He started to protest, but then the keys came out of his pocket and into her hand. She unlocked the trunk, put her shapeless white hospital coat inside it and took from the interior her plain black purse. She motioned for John Partlow to put the box in the trunk and he did as she indicated, noting that inside was a second cardboard box, a folded brown blanket and a gasoline can. As Ginger closed the trunk’s lid a hip and a shoulder pressed against John Partlow’s side, and he couldn’t help but feel a hot jolt of electricity pass through his body and seemingly crackle between his teeth.

“Climb in the back,” she told him, and Honeycutt looked at him with a dazed expression and asked, “Who are you?”

When they were in the car, with Ginger at the wheel, Honeycutt reached under the seat and brought out a silver flask which he immediately uncapped and began guzzling from. The smell of strong whiskey pricked John Partlow’s nostrils. He said, “You’ve got a smooth pitch, Doc.”

“Hm,” the doctor grunted, and kept drinking.

“What do you sell?” Ginger asked, as she fired up the Packard’s motor.

“Myself,” said John Partlow. “And a few Bibles on the side.”

“Hearse-chaser?”

He took his time in answering. “Maybe.”

“Hearse-chaser,” she said with certainty, and she gave a small and brittle laugh.

They passed the boarding house. Ginger did not slow down a half mile-per-hour. “Hey!” John Partlow said. “We just—”

“Settle down, Pearly. We’re goin’ for a little ride.”

His heart had started beating harder and his mouth had gone dry but he kept his calm, at least on the outside. “Listen, Ginger…I’m not worth the trouble. You want to rob me, you’re gonna find that—”

“You talk too much,” she said, and with one hand she took the flask away from Honeycutt’s mouth and gave it back to John Partlow. “Have a drink and relax, Pearly. This is not a robbery.”

“Pearly?” Honeycutt scowled and tried to find his flask, as if it had just disappeared by an act of Houdini. “Who the fuck is Pearly?”

“The man who’s gonna kill you,” said Ginger LaFrance, as the Packard followed its headlamps into the Louisiana dark.

Three.

After making this statement Ginger let out another sharp little laugh, and the drunk doctor gurgled and laughed too, but in the backseat the man who wore the name of John Partlow as one of his many disguises squirmed uncomfortably because he had heard the hard edge of truth in the woman’s voice.

They’d passed Henry Bullard’s garage where the sick Oakland was kept, and they were outside the limits of Stonefield on the winding country road that led in from the west. All was dark but the occasional glint of lamplight through a farmhouse window and the sparkle of stars above the summer treetops. “You can pull over and let me out here,” said the hearse-chaser, who suddenly wanted nothing to do with either hearses or chasing. “I’ll walk back.”

“That wouldn’t do,” the woman said. “A wife to ditch her fancy hubby on the side of the road? No, it wouldn’t do.”

“What’s the game?”

“Drivin’,” she replied. “Just drivin’, that’s all.”

“Where’s my drink?” Honeycutt asked, and leaned down to find it under the seat again. “My drink! Where’s my drink?”

John Partlow reached over and tapped him on the shoulder with the flask. It took the doc a few seconds for him to register what was tapping him, and then a few seconds more for his hand to curl around it. He drank again from it, noisily. John Partlow figured Honeycutt was only good for one thing anymore, and that was standing up on a stage reciting the sex talk he knew so well by memory; the rest of the man’s brain was shot to hell either by whiskey, old age or just plain hard living, and maybe all those put together.

“Stella?” Honeycutt said after another swig and a wipe of his mouth with the back of his hand. “Where are we?”

“I’m not Stella. I’m Ginger.”

“Who?”

“See what I have to put up with, Pearly? By day I have to feed him like a baby and by night I give him his bottle to suck on ’til he passes out. You say he’s got a smooth pitch? Sure he does. Only it’s been gettin’ ragged ’round the edges for quite a time now.”

“Uh

huh. Well, you can let me out anywhere.”

“Sellin’ Bibles as you do,” she said as the Packard negotiated a long curve between stands of forest. “You make a livin’ off that?”

“It’s hard work and it can go wrong in one shake of a pig’s tail. Listen…Ginger…wherever you’re goin’ and whatever you’re wantin’ to do, I don’t have any part in this. Hear me?”

“I like your company. We both do. Don’t we, Willie?”

“What? Fuck I know what you’re talkin’ about.”

“There you go,” she said to John Partlow, as if that explained it all. “I’m lookin’ for a road we passed on the way in. Should be comin’ up on the left in a minute.”

“I’ve gotta pee,” said the doc. “Aren’t we back at that damn place yet?”

“Soon,” she answered. “Real soon now.”

John Partlow sat frozen; he didn’t like how this show was moving along yet he could do nothing to stop its progress. Whatever was ahead, he realized that all control had been taken from him and it awakened old horrors in his soul.

“Here’s the road,” Ginger said, and she slowed the car and turned it off to the left, onto a narrow dirt track with dark forest on either side that seemed as impenetrable as granite walls. She kept driving, as curtains of dust churned up behind the tires. “Let’s just see where this goes,” she said brightly.

“You get a flat out here, it’s snake-eyes,” John Partlow said, and was shamed to hear the nervous quaver in his voice.

“Oh, I like to gamble. I’m a good gambler. Isn’t that right, Willie?”

He made a grunting noise around the lip of his flask.

In another minute or so the Packard’s headlamps brushed across the remains of what had been a farmhouse that was now falling to pieces and overtaken by brush and weeds, its roof collapsed. Ginger slowed the car to a crawl. Past the equally-decrepit hulk of a barn the woods boiled up again, and the dirt road petered out.

She stopped the car, turned the engine off, and they sat without speaking while the hot engine ticked.

“I guess,” she said, “this is as far as we go.”

“Let me out, I’m walkin’ back,” said John Partlow.

“Finish your drink, Willie,” she said. “Then we’re gonna take a little walk ourselves.”

The doc lowered his flask. He asked in a bewildered voice, “Where’s our place?”

“We have no place,” she answered. “Said you had to pee. Get out and do that, we’ll get on the road.”

“Listen,” said John Partlow, but he didn’t know what to add to that. “Listen,” he said again.

“Get out and go pee,” she told Honeycutt. “Those woods over there. Go on, darlin’.”

“Awful dark,” he said. “Where the fuck are we?”

“Lord have mercy,” she replied, as if to a frightened child with whom she had lost patience. “Okay, I’ll come around and hold your hand but I’m not aimin’ your dick for you.” She removed the key from the ignition but left the headlights burning. When she got out of the car she took her purse with her, and John Partlow saw her place it atop the hood. Then she came around to the door that Honeycutt was struggling to open, opened it for him and said, “Come on, let’s get this done. Pearly, I’ll need your help.”

“No, ma’am,” he said, and he pushed the seat forward that Honeycutt had just vacated so he could get out the passenger side. He stood beside the car and looked back along the dark road, his heart pounding. The insects of the night were putting up a symphony of chirrs and chirrups.

“Go on, then,” Ginger said. She was holding onto Honeycutt’s left hand with her right. John Partlow saw her reach into her purse with her left hand. It emerged holding a small but ugly .38 revolver. “Come on, Willie,” she urged, “let’s find us a place.”

“I can pee right here,” he said, his voice muffled and somehow faraway. He started fumbling with his zipper, but she pulled at him and got him walking toward the woods to the right of the car.

“What the—” John Partlow had to try again because the words had logjammed in his throat. “What the hell are you doin’?” He had the crazy sense that this was some kind of con game aimed at him, and he was supposed to react in a certain way to step into the sucker trap, and he should turn and run along the dirt track until he got to the paved road and he could wave down a car—if one ever came along—unless the dame shot him in the back before he could take two steps.

“I’m all right, Stella,” said Honeycutt, who had staggered and had to catch himself against a treetrunk. Then he said, painfully, “Somethin’ scratched me. I can’t see where I am.”

“Just pull it out and pee, then we’ll get on about our business,” she told him, and she let go of his hand and stepped back.

“Last time I go to Georgia,” he said as he unzipped and pulled himself out. He looked around, dazedly, and in the wash of the headlights John Partlow thought Honeycutt had a profile like the actor Barrymore and likely had been a handsome young man. “Where are we?” the doc asked, looking up as if questioning the stars.

Ginger didn’t answer. When the pistol fired with a sharp crack all the night insects went silent and John Partlow nearly let loose a cup of piss into his own trousers. But even as Honeycutt cried out, clutched at his side and fell into the underbrush John Partlow thought sure this must be a con rigged to snare him up in something, but what the game was he could not see.

As the fallen doctor tried to crawl through the brush, Ginger walked back to the car with the smoking gun in her hand. She went to the trunk, unlocked it and reached around until she found what she was looking for. She turned the flashlight’s beam on and held it out to John Partlow. “Take it,” she said. “Come on and hold it on him.”

“I’m not here,” he answered, shakily.

“Really?” Her champagne-colored eyes fixed upon him. “Well, I was gonna give you the car if you want it, but if you’re not here I guess that won’t wash.”

“The car? Why would I want the car?”

“Because it’s a nice car, nearly new, and the papers are in the glovebox.” She paused, glancing back at Honeycutt as he gave a terrible moan, then she returned her focus to the hearse-chaser. “I figure you’re a smart man with the resources to get your own name on those papers. What is your real name?”

“John Partlow.”

“I can smell an alias. Try again.”

“John Partner.”

“Ha,” she said quietly. “That’s even more made-up than the first. Try again?”

“John Parr.”

She studied him in silence for a moment. “I think,” she said, “that you’ve got even more names than me. I’ll just call you Pearly, how about that? You can put what you like on the papers. Come on, hold this light and let’s get his wallet before there’s too much blood on it.”

“Are you crazy? Absolutely fuckin’ out of your mind? You just shot a man! Likely he’s gonna lie there and die!”

She nodded. “Yeah, that’s the picture.”

“The police will take your goddamned picture after you fry in the hot chair! You’ve got to be nuts, doin’ somethin’ like this!”

She rested the barrel of the .38 against her chin. “Listen, Pearly, here’s the scoop: I’ve been with the doc for the last two years, travellin’ around doin’ these shows. I took over from the last girl, Stella by name. She told me how bad off he was gettin’, that he was on his last legs even then. I stuck with him, though, ’til I figured out I wasn’t meant to be a nursemaid to a sixty-eight-year-old man losin’ his marbles. Oh yeah, he could throw the pitch, sure he could. But otherwise he’s got so many bats in his fuckin’ belfry it would scare the shit out of Dracula. Now—you bein’ a man of the road as I’m gamblin’ on you to be—how do you want to end up? You want to fade away sittin’ in a room droolin’ in your soup? Peein’ in your bed and not knowin’ you’re lyin’ in it ’til somebody tells you? You want to go out simperin’ and stupid, not knowin’ what day

it is but just that the hands on the clock don’t hardly ever move? Or you want to go out fast…like…” She thought for a few seconds. “Like Bonnie and Clyde,” she said. “Leavin’ a trail of fire. Bein’ remembered,” she said. She motioned with the gun toward the man in the weeds. “He’s got no family. Well, a daughter in California but she’s married and on her own, he never hears from her. So if he was in his right mind he would be the first to say he wanted to be cut loose from this goddamned world. Cut free, if you believe anything the preachers say. And you bein’ a Bible seller and wearin’ a tieclip like you’ve got on, you’ve got to see in the eyes of the people you sell to that they believe there’s somethin’ better than…” She looked around at the woods. Honeycutt had begun to quietly sob. “This,” Ginger finished, with a hint of a sneer.

“Oh, yeah,” Pearly said, returning the sneer. “Tell the cops it was a mercy murder, they’ll fall down on their knees and make you a saint.”

Incredibly, she gave him the slightest smile and her eyes seemed to shine. “What do the cops know about any damned thing?” she asked.

It was a warm night. Pearly felt the sweat trickling down under his arms. He felt a damp sheen on his forehead beneath the brim of his white straw fedora. The insects were starting to whisper and thrum again, and it sounded to him as if the night were asking him a question: What are you going to do…to do…to do…to do…?

“Help me,” Ginger said, and pressed the flashlight against his right hand.

Did he remember taking it? Or did he just remember how her face looked in that moment, as if she already knew everything about him, everything he tried to hide, all the secrets? When she looked at him with those champagne-colored cat eyes he thought she could see right to his beginnings of being the baby that everybody hears about but nobody knows, the kid left in a basket on the church steps a couple of hours before early Sunday service, and then on into the maelstrom of foster families, one after the other and none of them worth a damn, on into the never-ending storm of being a beautiful boychild that some people wanted to use and some people wanted to use others with, and on and on into the early and terrible realization that no one was on your side in this world, nobody gave a shit about you and nobody was going to feed you when you were hungry or hold your hand when you walked where the angels feared to tread, so mama don’t give this man no money because no one was to be trusted and mama don’t give this man no money because the only value of a name was as a disguise and so he had gone through many of them, many disguises and many masks, and down deep where the ashes lay ever-smouldering in the burnt-out cellar of his soul he had the satisfaction of being smart and quick, a survivor to the core.

Swan Song

Swan Song The Wolfs Hour

The Wolfs Hour Ushers Passing

Ushers Passing Mine

Mine The Queen of Bedlam

The Queen of Bedlam Baal

Baal Boys Life

Boys Life Speaks the Nightbird

Speaks the Nightbird The Hunter from the Woods

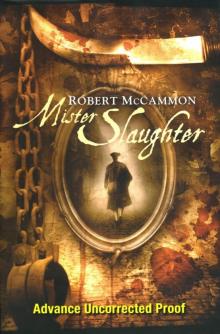

The Hunter from the Woods Mister Slaughter

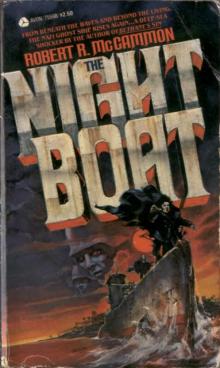

Mister Slaughter The Night Boat

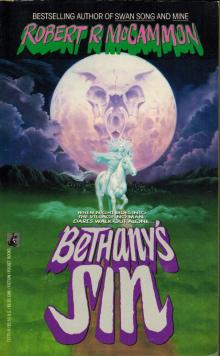

The Night Boat Bethanys Sin

Bethanys Sin Mystery Walk

Mystery Walk Gone South

Gone South Cardinal Black

Cardinal Black I Travel by Night

I Travel by Night Last Train from Perdition

Last Train from Perdition 1987 - Swan Song v4

1987 - Swan Song v4 The River of Souls

The River of Souls The Border

The Border 1990 - Mine v4

1990 - Mine v4 1988 - Stinger

1988 - Stinger The Listener

The Listener