- Home

- Robert McCammon

The Night Boat Page 8

The Night Boat Read online

Page 8

Chapter Seven

HE PAUSED IN the darkness, took from a back pocket a flask and uncapped it, tilted it to his lips, and let the good strong Blackjack rum flow down. Then he wiped his mouth on his sleeve, returned the flask to the pocket, and continued walking the road.

The darkness was absolute, the midnight breezes thick. They clung around him. No lights burning in the village. Everyone asleep. No, no - there was a light burning up at the Indigo Inn. A single square of light in an upstairs window. He didn't know the white man, but he'd seen him around the village before. It was the white man found the submarine.

The jungle grew wild just beyond the road; cicadas were singing like sawblades in the trees, and every now and then a bird skreeled. It was just enough noise to unnerve him. Out at sea there was only the blackness; he could hear the surf on the coral and he knew the beach was near, but he couldn't see it.

He'd gone back to the naval shelter three more times that day to look at the U-boat, to think about what might be waiting for him inside. The gold bars found in Cayman waters had flamed his greed. Of course, he didn't know if the stories were true or not - he'd heard them from a rum-rag in a bar - but if it was true! It was. It had to be true. He quickened his pace. The boatyard was around the next curve in the road, and he had hard work to do.

Something about that vessel had eaten into Turk; there was a strangeness to it, he had a weird feeling about it. He'd spent all day thinking about it, wondering what treasures it could be hiding. Maybe that damned policeman knew more than he was saying, too. Why else would he have wanted to put it away inside that shelter? Why not just let it rot in the harbor? No, somethin' was real strange. The policeman was hidin' somethin'. And nobody had ever hid any secrets from Turk Pierce.

The whitewashed wooden gates to the boatyard entrance were straight ahead. It would be easy to either slip under them or climb over. Hell, who was going to know? He had almost reached them when a shadow detached itself from the other jungle shadows and stepped out into the road.

Turk stopped, frozen, his mouth half-open.

In the darkness the apparition was huge, a hulking form with wide bare shoulders, its chest covered by the thinnest cotton shirt. He took a step back before he realized it was real - it was a man. He was bald-headed, his flesh a tawny color instead of pure ebony; he had a white beard and mustache, cropped close to his shadow-covered face, and Turk caught the sudden gleam of a small gold ring hanging from one earlobe. The man was carrying a crate of some kind, and Turk could see the muscles defined on his forearms. The figure stood perfectly still, watching.

"Hey, you scared the fuck out of me," Turk said easily, trying to control his voice. Christ! He didn't want any trouble, especially not with a bastard as big as this. "Who are you?"

The man said nothing.

Turk stepped forward, trying to see the face, but the figure had vanished, swallowed up by the foliage. A knot had caught in Turk's throat; he thought he'd seen one side of the face, and it had been a hideous mass of scars. He stood still for a long time, then took his flashlight from his belt and shined it into the jungle, cautiously. Nothing there. If the man was still around, he was moving silently. Turk shivered, fighting off a cold wave of nameless fears. What was that thing, a damn jumbie walking the road maybe hunting a soul? Something lookin' for a little child to suck the blood out of?

He kept the light on, moving it from side to side before him. When he reached the gates, he saw there was enough room for him to slide beneath them on his belly. Crossing the yard, moving through discarded piles of machinery, empty oil barrels, around beached boat hulks, he saw the naval shelter. He paused for a moment, standing against a mountain of cable, and switched off his light. He'd heard a noise, like the sound of someone walking along wharf planking. A goddamn night watchman? There was the noise again, and then Turk realized it was just the breeze, slapping the weathered boatyard sign against its support posts. He could hear the sound of the clangers in the far distance, and the bass rumble of breaking waves. Turk snapped his light on again, still uneasy from his encounter with that figure on the road, and approached the shelter. Cochran hadn't put a chain or padlock on the door, thank God; it was closed, a few crates blocking it. A handpainted sign read: Keep out. Cochran.

Turk pulled the crates away, scowling when he found they'd been filled with heavy odds-and-ends - bolts and broken tools. He opened the door, shined the light around inside, then entered. It smelled like a burial vault and the stench was almost overpowering, but he swallowed and tried to keep his mind off it. Light reflected off the water and rippled across the walls, undulating beneath the thing's hull. Strange shadows moved away from the beam of light, like phantoms scurrying for the safety of darkness. He worked the light over the conning tower, up to the tops of the shafts, and then back along the superstructure. You ain't so much hell now, are you? he asked the thing. Something clattered sharply behind him, and Turk sucked in his breath; he flashed the light into a corner, his heart hammering. It was only a rat, panicked by the unfamiliar light, squeezing among a clutter of oil cans and rag scraps.

There was a gangplank between the concrete walkway and the U-boat's deck, and Turk crossed it, careful of his footing. He had already climbed to the bridge and examined the main hatch there during the day; water and sand more than an inch deep still swirled over it. There was another hatch on the aft deck, covered with the tendrils of cables, and he couldn't work them away alone. But on the fore deck, near the gun's snout, there was a third hatch, the seam line marking a large rectangular opening. It was covered over by a broken planked lid.

Turk bent down, his eyes following the circle of the light, and lifted the hatch cover to examine the iron again. How thick would this bitch be? he wondered. He banged a hand against the iron and knew it was going to be a hell of a job. He sat back on his haunches and swung the light toward the spear-point of the bow far ahead. Hell of a big mothafucker, he thought. His impulse to burn through was stronger than ever, though he was oddly unnerved by the sheer size of the boat. There was probably no gold inside, but what about souvenirs? he wondered. The dealers in Kingston and Port-au-Prince could move anything. And there was a collector for everything under the sun. He might be able to get a good price for some of the equipment inside, maybe find himself the skeleton of a pistol or intact instrument gauges. And what about bodies? Maybe they in here, may they ain't. Come on, come on; you got a job to do.

Something made a noise on the other side of the shelter; Turk swung his light around, swearing softly. The rattle of a can. The flashlight beam shone through thick clumps of brown weed that hung down from the tower bulwark, and he could smell the sea in them. Another rat, Turk told himself. The shelter was filled with the things, big bloated wharf rats that ate the dockside roaches. He'd best get on with it.

Hidden back in the carpentry shop, covered by an oily tarpaulin, was a cylinder truck - an apparatus like a pushcart - with a cylinder of acetylene gas and a larger cylinder filled with oxygen. From the two cylinders there were hoses that connected to the welding-torch unit, providing a flammable mix of the gas, in this case, for the cutting process. Turk had wheeled the unit over to the shelter just before quitting time and had hidden it in the carpentry shop. He was taking a chance, if Cochran had decided to take a check of the supply shed, but the worker in charge of the equipment was a lazy bastard, Turk thought. Which had worked out fine for him.

Now he wheeled the truck over the gangplank onto the deck, carefully because it was fairly heavy and the planks groaned beneath its weight. He got the truck positioned as he wanted it before putting on the welder's mask he'd left hanging on the truck frame. Turning on the valves to release the gas and oxygen flow, he used his striker to spark the torch tip and it sprang into life, a soft orange glow in the darkness. He adjusted the mix until he was ready, then bent down and began to work, his hand moving in a smooth semicircular motion.

Over the soft hissssss of the burn

ing gas he heard the great boat moan, like a sluggish and heavy creature awakening from sleep.

In the small bedroom of a brown-painted stucco house across the island, Steven Kip jerked suddenly and his eyes opened.

He lay very still, listening to the repetitious voice of the surf, wondered what it was that had awakened him. Beside him his wife, Myra, was sleeping peacefully, one slender arm thrown out across his chest, her body pressed against his side. He turned his head and kissed her very softly on the cheek, and she rustled the sheet and smiled. They had been through a lot together, and though the years had made Kip tougher and more cynical, they had been gentle with her. There were laugh lines around her eyes and mouth, but they were lines of good living. He kissed her again. He was a light sleeper, so anything could have awakened him: a wave breaking, the clatter of a coconut palm, the shrill of a nightbird. He waited for a few moments. Still nothing. All familiar sounds he had heard a thousand times before. He lay his head back on the pillow beside hers, and closed his eyes.

Then he heard it again.

A muffled stacatto of drums, echoing from somewhere distant.

He sat up, drew the covers aside, and rose from the bed. Myra stirred and lifted her head. "It's nothing, baby," he whispered. "Go back to sleep. I'm going to have to go out. "

"Where are you going?" she asked, rubbing her eyes. "What time is it?"

"After three. Lie back now, and sleep. I won't be long. " Already he was getting into his trousers, then buttoning his shirt. Myra pulled the sheet up around her, and Kip crossed the room to peer out through a window that faced the harbor. It was pitch black out there except for the stars, tiny clusters of light in the sky like the wheelhouse lanterns of a thousand spectral ships against a black ocean.

Then, again, echoing through the jungle, the sharp rattle of the drums; Kip's skin tightened at the back of his neck. Damn it to hell! he thought, pulling on his shoes and leaving the house as quietly as possible.

He drove the jeep to Front Street, turned along the dark shanty village on the harbor rim and toward the jungle, the wind sharp in his face. He watched the windows for lights and searched the streets for moving figures, but no one was stirring. Who else was listening to those drums? How many lay in the dark, eyes open, trying to read the message that was swept across the island with the early breezes? Kip knew what it had to be: Boniface conducting a ritual over the boat. Damn the man! Kip cursed silently, still watching for lights. I'm the law here, the only law, above and beyond Boniface's voodoo gods.

Along Front Street where the jungle bent down low in strange shadowy shapes, he saw several men standing in the road. When his headlights touched them they twisted away before he had a chance to recognize any of them. They leaped into the surrounding underbrush and were gone in a few seconds. When Kip came to the church, he found it darkened and deserted. He stopped the jeep and sat there for a few moments, listening. When the next brief flurry of drums came, still somewhat distant, Kip caught their direction. He took a flashlight from a storage box on the rear floorboard, clicked it on, and climbed down from the jeep.

There was a narrow path leading past the chicken coop and Kip walked along it as silently as he could, the thorns catching at his shirt. The jungle was densely black on all sides and quiet but for the persistent, steady drone of insects. In a few more minutes he could hear fragments of voices, the sudden crying out of what sounded like several women at once, the forceful voice of a man, all punctuated by sudden bursts of the rapid drums. He went on, following the path even when he was forced to crawl beneath a thick cluster of wiry brush. The voices became progressively louder, more frantic, and at last he caught a glimmer of light ahead. The drums pounded a steady rhythm, three or four patterns intertwining, louder and louder, each beat accompanied by a scream or a shout as if the drums themselves were crying out in either pain or ecstasy. The noise grew until the drumming was inside Kip's head, a wild and unconfined frenzy of sound. And through the drum voices there was the voice of a man, rising from a whisper to a shout: "Serpent, serpent-o, Damballah-wedo papa, you are a serpent. Serpent, serpent-o, I WILL CALL THE SERPENT! Serpent, serpent-o, Damballah-wedo papa, you are a serpent. . . "

The jungle was suddenly cut away to make a clearing; Kip quickly turned off his light and stayed hidden in darkness. Blazing torches formed a wide circle around a small three-sided, straw-roofed hut. Directly in front of the hut, surrounded by black and red painted stones, was a fire that licked up toward the jungle ceiling high overhead. A strange geometric figure had been traced in flour in front of the fire, and placed at points on the figure were various objects: bottles, a white-painted steel pot, a dead white rooster, and something wrapped in newspapers. The drummers sat behind the fire, and thirty-five or forty people made a ring around them - some lying on their bellies in the soft dirt, some twirling madly in circles, still others sitting on the ground, staring with open, glazed eyes into the depths of the flames. The drumming was furious now, and Kip saw beads of sweat fly off the half-nude forms that circled the fire. One of the dancers lifted a bottle of rum and let the liquor pour down into his mouth, then he doused the rest of it over his face and head before spinning away again. Empty bottles lay scattered about. Sweat streamed from faces and over torsos, and Kip caught the powerful smell of strong, sweet incense in the air. One of the dancers whirled in and threw a handful of powder into the flames; there was a burst of white and the fire leaped up wildly for a few seconds, illuminating the entire clearing with red light. A man in a black suit leaped in the air and crouched down at the base of the flames, shaking a rattle over his head. It was Boniface, the fires glinting off his glasses. Sweat dripped off his chin as he shook the rattle and cried out, "Damballah-wedo papa, here, Damballah-wedo papa, here. . . "

A woman in a white headdress fell down beside him, her chest heaving with exertion, her head revolving in circles and her eyes glistening with either rum or ganja. She lay on her belly, snaking along as if she were trying to crawl into the flames. It was the Kephas woman, the same woman Kip had seen that very afternoon sitting in a dark corner of her house muttering something he had failed to understand.

Boniface shook the rattle, now in time with the drum beating, and reached into the white pot with his free hand to withdraw a thick snake that instantly coiled about his forearm. At the sight of the snake there was a chorus of screams and shouts. He held it up, crying out, "Damballah-wedo papa, you are a Serpent. Serpent, serpent-o, I WILL CALL THE SERPENT!"

Kip's heart was hammering, his head about to crack from the noise. The drummers stepped up their rhythms, the muscles standing out on their arms, droplets of sweat flying in all directions. Kip could barely hear himself think; the screaming and the drums were bothering him, reaching a part of his past he had closed tight, to a place of fearful memories and grinning faces hanging from straw walls. Boniface turned and draped the writhing snake around the woman's shoulders like a rippling coat, and she cried aloud and stroked its body. The reverend put aside his gourd rattle, lifted the object wrapped in papers over his head and began to spin in front of the fire, shouting out in French. The old woman let the snake slide from arm to arm. She played with it, teasing it with a tetettetette noise. Boniface lifted a bottle of clear liquid, poured it into his mouth and held it there while he unwrapped the object. In the light of the fire Kip saw it was a crude wax image of the submarine; Boniface tossed the paper into the flames and sprayed the image with the liquid from his mouth, and as the others shouted and urged him on he held his hands out to the fire, his eyes wild and his teeth bared in a grimace. In another moment the heat began to melt the wax, and Boniface began to knead the image until wax dripped down his hands and arms. When nothing was left but a misshapen blob, he cast it into the fire and stepped back. The others screamed louder and danced like possessed souls. Boniface spat into the fire.

The old woman stared into the face of the snake, then lifted her chin and let it explore her lips with its questin

g tongue. She met the tongue with her own; they seemed like nightmarish lovers. When she opened her mouth to let the reptile probe within, Kip could take no more and stepped out into the light.

One of the drummers saw him first; the man gaped and faltered in his rhythm. The others noticed at once; heads turned, and someone shrieked as if in pain. A few of the dancers leaped up from the edge of the fire and ran for the jungle. The Kephas woman looked at Kip in horror, the snake slithering from her arms into the grass, and then she too ran away, her skirts billowing behind her. The rest of them were gone almost at once, the jungle closing behind them, the darkness swallowing them up.

And in the silence, still echoing with the beat of the drums and the shouting, Boniface stood framed against the fire, staring across the clearing at the constable. "You fool," he said, trying to catch his breath. "It wasn't yet complete!"

Kip said nothing, but walked to the edge of the fire. He examined the assortment of bottles. One of them looked as if it were half-filled with blood.

"IT WASN'T YET COMPLETE!" Boniface shouted, his hands curled into fists at his sides.

There was another pot filled with water; Kip picked it up and poured it over the blaze. The timbers hissed and smoke twisted toward the sky. "I've let you carry out your ceremonies," he said quietly. "I haven't raised a finger to interfere. But, by God" - he turned to face the other man - "I'll not have you making something out of that boat and the old man's death. "

"You young ass!" Boniface said, wiping beads of sweat away from his eyes. "You don't understand, you could never begin to understand! You fool!"

"I asked for your help. " He kicked at the embers and dropped the pot to one side. "Is this how you're helping me?"

"OUI!" Boniface said, the anger white-hot in his eyes. He held Kip's gaze a few seconds longer, then looked back into the remains of the fire. His shoulders were stooped, as if he had been drained of all strength. "You can't see, can you?" he asked, in a tired whisper.

"What was the Kephas woman doing here?"

"It. . . was necessary. "

"God, what a shambles," Kip said, looking around the clearing.

"All necessary. "

"I don't want any trouble, Boniface. I thought I made that clear. . . "

Boniface glared at him sharply, his eyes narrowing. "You and the white man are to blame. Both of you brought that thing into the boatyards. Now you are to blame!"

"For what!"

"For what may take place if I'm not allowed to take a hand against it!"

Kip looked down into the glowing remains of the fire and saw the clump of wax there, blackened by the heat and ashes. He kicked it out into the grass and looked across at the reverend. "What kind of madness is this?"

"I expected better from you," Boniface said bitterly. "I expected you to be able to see. The white man, no, but you, Kip. . . you could open your mind if you wished, you could feel it. . . "

"What are you saying, old man?" the constable asked him harshly.

"I know about you; you think you can hide it but you're mistaken!"

Kip took a step forward. "What are you saying?"

Boniface stood his ground; was about to explain but then thought better of it. He bent down and began to gather up the bottles that stood along the lines of the geometric figure. He put them down into the white pot that had contained the snake, and they rattled together.

"What do you know about me?" Kip asked very quietly.

The reverend began to smear the geometric lines with his foot. "I know," he said without looking up, "who you could have been. " His head came up, and he stared fiercely into the constable's eyes. A strange, almost tangible power riveted the other man where he stood. He could not have moved even if he'd wished.

"Listen to me well," Boniface told him. "If you refuse to take the boat to deep water, you must do these things: Lock that shelter securely. Let no man go near it. Let no man touch his hand against that iron. And for all our sakes do not try to break the hatches open. Do you understand what I say?"

Kip wanted to say no, that Boniface was a raving fool, that the man didn't know what he was talking about, but when he spoke he heard himself say, "Yes. "

And in the next instant the reverend was gone, melting away into the darkness beyond the circles of torchlight. Kip had not seen him turn to go, nor did he hear the man making his way through the underbrush; he had simply vanished.

Gradually the night sounds returned, filling in the spaces left when the drums and the shouting had stopped. Insects called to each other across the jungle, and the cries of the nocturnal birds sounded like the voices of old men. Kip covered the embers with dirt until he had completely extinguished the fire, then clicked his light back on and retraced his path to the jeep. There was a yellow glimmer of a light behind a window shutter at the church and a shadow moving about within.

He climbed behind the wheel and started the engine. He was actually eager to get away from this part of the island; it was Boniface's kingdom, a place of shadows, jumbies and duppies, faceless things that walked the night seeking souls. He drove back toward the harbor, along Front Street and through the village. Still no lights, no sounds. And before he realized it, he had passed the road leading toward his house and was driving to the boatyard as if drawn there by something beyond his control. There was a sheen of sweat on his temples and he hastily wiped it away. He couldn't shake the image of Boniface, standing before him, touched with amber light that glittered in his thick glasses. I know, the man had said, who you could have been.

And then Kip's foot came down hard on the brakes.

The jeep started to spin in the sand, but Kip let the wheel turn and then corrected its direction; the jeep straightened, whipping grit up behind it, and then stopped abruptly as the engine rattled and died. Kip sat and looked straight ahead for a long time.

The boatyard gates were shattered, the weathered timbers broken and lying splintered on the ground. The timbers that still remained in the gate sagged forward, like bones in a broken rib cage, their edges raw and jagged.

An ax, Kip thought. Some bastard has taken an ax to Langstree's gates.

He picked up his light, climbed out of the jeep, and went through into the yard. Nothing else seemed to be wrecked, though in the disarray it was difficult for him to tell. He swept his light in an arc. Nothing moved. There was no noise but for the sea and the slow creaking of a boat moored to the wharf. This would be the right time for someone to break in, with Langstree away. Why the hell didn't the man hire a watchman? That cheap old bastard! he thought angrily, knowing it was his own responsibility if someone had made off with something valuable.

As he moved deeper into the yard, he tried to keep his mind off the U-boat ahead in the naval shelter. The image of the rotting thing was a searing flame in his mind. He moved past a great heaping tangle of ropes and cables and walked faster, heading directly for the shelter.

He saw immediately that the door was open; he stopped in his tracks, shining the light about, and then slipped through into the stench of decay. He moved his light slowly along the hulk, not knowing what to expect, not even knowing what he was looking for. And when the beam picked out the form of. the cylinder truck on the forward deck he swore and let his breath out in a hiss.

As he crossed the gangplank he shined the light down onto the deck, and then he saw the gaping, smooth-edged void where the hatch had been burned out. The hatch itself, the bottom of it encrusted with some kind of yellow fungus, lay several feet away on the deck. Kip thrust the light down toward the hole, aware that his heartbeat had picked up, that there was something. . . something. . . something. . .

Aware that blood was splattered around the yawning opening.

At once Kip sucked in his breath, stunned. He bent down and touched a hand to the thick globs of blood. He wiped it off on his trouser leg. The blood was so dark it was almost black, and he realized he was standing in it. Puddles had c

ollected around the hatch opening like oil seepage. And now he smelled it as well, like a thick, coppery taste in his mouth. There was a larger lump of something beside him, and it was only when Kip had bent to examine it that he realized it was a piece of black flesh.

The U-boat moaned softly, and a timber creaked, the echoes filling the inside of the shelter. He turned, played the light up the conning-tower bulwark and toward the stern. A sharp, piercing fear was inside him, jabbing at his guts, and he fought to keep hold of his sanity. He backed away from the hatch, keeping his light on it, until he'd reached the gangplank.

The flashlight beam played across the murky green water: A Coke can floated against the hull, and beside it a beer can. The water, pulled in through the sea bulkhead, was dotted with cigarette butts, and his light touched the staring eye of a white, bloated fish. Something else was there as well, floating just under the gangplank at Kip's feet.

A welder's mask.

Kip got to his knees, reaching down with one hand to pull it from the water. And as he did and the mask came free, the body underneath it rose to the surface. The eyes were wide and terror-stricken, the open mouth was filled with water. Beneath the battered face the throat had been torn open. Bare bone glittered in a red, pulpy mass that had been a larynx and jugular vein. Half the face was peeled back, the teeth broken off or ripped from the mouth. The arms floated stiffly at the corpse's sides, and already tiny fish were darting in to taste the blood at the mangled throat.

Kip cried out involuntarily and pulled his hand back, the welder's mask dangling from his fingers. The body began to turn in a circle, bumping against the side of the basin. Kip felt the place closing about him, felt the darkness reaching, and beyond the darkness things that grinned and clawed at him with filthy bloodstained fingers. He backed away from the U-boat, his legs like lead, and then half-walked, half-ran into the fresh air outside, drawing breath after breath to try to clear away the sight of that dead, gray-fleshed face.

"My God," he muttered brokenly, supporting himself against the shelter wall. "My God my God my God. . . "

For he had recognized the expression on Turk's dead, puffed face. It was a glimpse into an unnamable horror.

Swan Song

Swan Song The Wolfs Hour

The Wolfs Hour Ushers Passing

Ushers Passing Mine

Mine The Queen of Bedlam

The Queen of Bedlam Baal

Baal Boys Life

Boys Life Speaks the Nightbird

Speaks the Nightbird The Hunter from the Woods

The Hunter from the Woods Mister Slaughter

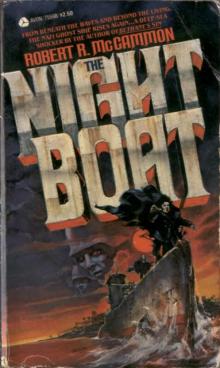

Mister Slaughter The Night Boat

The Night Boat Bethanys Sin

Bethanys Sin Mystery Walk

Mystery Walk Gone South

Gone South Cardinal Black

Cardinal Black I Travel by Night

I Travel by Night Last Train from Perdition

Last Train from Perdition 1987 - Swan Song v4

1987 - Swan Song v4 The River of Souls

The River of Souls The Border

The Border 1990 - Mine v4

1990 - Mine v4 1988 - Stinger

1988 - Stinger The Listener

The Listener